First question most people will have is, what’s biomass? Let’s get that out of the way before we go any deeper. Biomass is any material of biological origin, as long as it’s not been buried in the ground for millions of years—that caveat is what makes it renewable. So it’s plant matter like wood, hay, and seaweed, but also fungi and animal matter. When chemists are talking about biomass, it’s usually the plant side of things.

Biomass is (rather obviously) absolutely vital to our life on this planet. It forms ecosystems, sequesters carbon, and provides food to eat and raw materials (feedstocks) for making things out of. We already use it in abundance across sectors like construction, energy, furniture, and textiles.

We’re currently undergoing a drastic change in the way we use biomass. Demand for biomass for materials and energy usage is growing in tandem with the shrinking demand for petrochemicals. Current EU climate scenarios project a biomass need of 40-100% more than we have available—that is, there is going to be massive competition for use of the biomass that we produce.

With high competition for biomass, we need to optimise its use, making sure everyone gets what they need without destroying our remaining vibrant ecosystems.

Biomass has a huge variety of uses, with a beautiful chemical complexity that we are only beginning to learn to access. The polymers made by nature are so much more interesting than what we can make with conventional chemistry, and have huge potential to replace building materials, packaging materials, cosmetic ingredients, and so on. Even in an application as fundamental and ancient as using wood to build things, we’re still making huge advances in knowledge today—just check out the mass timber “plyscrapers” going up in Tokyo and London.

So optimising our limited biomass, putting the right natural material to the right use without waste, will require some careful strategic planning! Luckily, the UK has a Biomass Strategy that it published in 2023. Unluckily, the “strategy” is to burn biomass for energy, regardless of whether that makes economic or sustainable sense.

The UK Biomass Strategy focuses on burning biomass

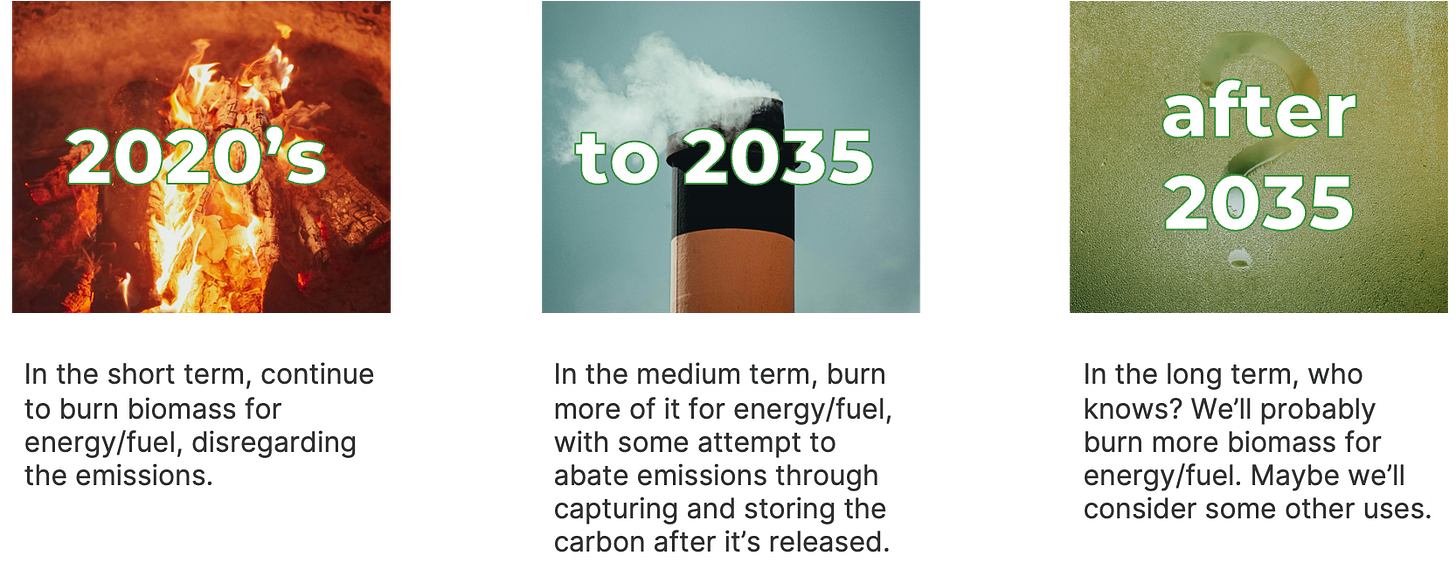

There are three stages to the biomass strategy: burn it without a care, burn it with some amount of care, and then, who knows?

The Biomass Strategy also admits that the way we burn biomass for energy is not currently sustainable. In a 2021 call for evidence, only 38% of respondents felt that the current sustainability criteria for biomass energy were sufficient. The strategy lays out some plans for strengthening the criteria, but never asks whether burning biomass actually makes any sense at all.

Burning biomass for energy doesn’t even make financial sense

Warning: some math ahead. Skip ahead to the next section if you don’t like plots.

You can calculate the economic value of biomass a few different ways. Could you sell it as food or feed? How much will people pay for the energy that comes from it? How much is it worth if you use it as a carbon store?

Let’s look at those last two. One tonne of biomass can be converted to 18 gigajoules of energy, or used to store 1.8 tonnes of CO2eq.

The energy is worth something, and its value can be compared against value of more popular energy feedstocks, like coal and gas. The carbon storage is also worth something, but a bit harder to quantify. You can look at emissions trading schemes (ETS) or carbon taxes to get some idea of the USD value of a tonne of CO2eq:

In short, the value of carbon is growing rapidly, and will continue to grow as climate breakdown intensifies.

So by using the above numbers, you can plot the value of biomass as a carbon sink, and identify the point at which the carbon-removal value is higher than its energy value. That’s exactly what some researchers at Lawrence Livermore National Lab did in 2020. Don’t worry, I’ve pulled the report’s key plot out for you here, and even marked some European carbon prices on it for you.

On the X-axis, you’ve got carbon price, which you multiple by the 1.8 tonnes of CO2eq a tonne of biomass can store to get a nice straight line—as carbon price goes up, carbon removal value goes up.

The horizontal lines are 2020 prices for some energy feedstocks, converted to be equivalent to the 18 GJ of energy you’d get from the same tonne of biomass. So when carbon prices hit $30, the carbon removal value of biomass is worth more than people would pay for an equivalent amount of coal. When carbon prices hit $70, the biomass’s carbon removal value is more than people would pay to get energy from oil.

So burning biomass for energy doesn’t make financial sense, because the carbon storage it provides is worth more than the energy. Unless you also harvest the carbon using some sort of, say…carbon capture technology?

BECCS won’t save us

The ever-moving promise from biomass burners is that they’ll just capture the CO2 emitted from burning biomass, and stash it away somewhere deep underground, getting the best of both worlds (bioenergy with carbon capture and storage, or BECCS). It sounds great, but there are a few problems:

Capturing carbon is very energy-intensive, and can increase fuel requirements for a power plant by over 30%—so with BECCS you’d burn more biomass and get even less energy value from it

BECCS is expensive, with estimates ranging from $40-1000/tonne CO2 captured. So you might have to pay more than the carbon is worth just to capture it.

BECCS is risky and would need a lot of careful verification across the supply chain to make sure that it’s actually storing carbon, and there’s no leakage or, say, cutting down of primary growth forests to make wood pellets to burn…

BECCS doesn’t exist yet. Drax started promising BECCS in 2018, and now plans to fit at least one BECCS unit by 2030, but why are we pouring money into this unproven tech when better, cheaper solutions already exist?

When the wind stops blowing and the sun stops shining, we don’t need to burn wood

Grid-scale energy storage is not new—you can pump water up a hill when power is cheap, and let it back down when it’s expensive, for example. There are so many proven technologies that can store renewables—we just need to deploy them.

We have access to cheaper batteries now than ever before, and while going full lithium creates its own sustainability issues, there are new chemistries being developed all the time—like Donald Sadoway’s molten salt batteries, which can be made with earth-abundant, local materials. If your energy storage doesn’t need to be lightweight, there’s a whole world of options.

From 2002-2023, the UK government gave £22B of support to private businesses burning biomass for power and heat. By contrast, the entire Faraday Battery Challenge, which is a record investment in battery research and innovation, has £610M of support over 2017-2025—per year, less than a tenth of the amount given to biomass burners. Imagine what kind of solutions we might have by now if the £22B were given to develop energy storage, for “when the wind isn’t blowing and the sun isn’t shining”, as Drax is so fond of saying.

Experts agree that biomass policy is misaligned with economics and sustainability

It’s not just chemists clamoring to use biomass more intelligently. A wide range of experts have been saying for years that subsidising unabated burning of biomass (or indeed, burning biomass at all) is unsupportable.

The Climate Change Committee (CCC), an independent public body that advises the UK governments on tackling climate change, advised in 2018 to stop providing these subsidies:

“Do not provide further policy support (beyond current commitments) to large-scale biomass power plants that are not deployed with CCS technology.” (CCC, 2018)

Material Economics, an arm of the strategic consultancy McKinsey, wrote a 2021 report on EU Biomass Use in a Net Zero Economy. They were seeking to derive the greatest possible value from biomass (e.g. use it in the best way) during the net-zero transition. As part of this report, they highlighted that the economics of biomass use is being changed by government policy, and its use as a material should be more valuable than its use for energy:

“Unless prices are distorted by policy, the materials properties of wood and fibre are intrinsically more valuable than their mere energy content.” (Material Economics, 2021)

Finally, the LLNL analysis I mentioned above started out looking for the best ways to deploy BECCS and ended up concluding that BECCS was a fundamentally wrongheaded approach. If we’re trying to prevent climate change, we need to maximise carbon removed from the air, not burn the biomass and then worry about emissions.

“…if the goal is to remove CO2 from the air and store it long-term, the focus should be on maximizing the carbon removed from the air while minimizing costs and promoting other beneficial activities.” (LLNL, 2021)

We need to rethink how biomass is used

The biomass policy cannot be “let’s burn biomass now and worry about it later”. Climate breakdown has gone too far already, and we need to pull every lever we have to turn it around. That means doing something with biomass that makes both economic sense and sustainability sense.

Can we develop a biomass policy that isn’t captured by industrial interests, and instead guides us in getting the best value out of biomass? Here’s my proposal:

As in the waste hierarchy, reduce waste above all. Improve the circularity of our agricultural system by reducing food waste and turning byproducts into feedstocks.

Emphasise the unique value of biomass in providing us with useful molecules and locking away carbon.

What would this look like? Maybe something like this: a biomass hierarchy.

Food is essential and we can only get it from biomass, so that’s priority number one. Next, long-lived products that displace energy-intensive materials while locking the carbon away—think constructing buildings from wood instead of cement.

After that, it gets a bit fuzzy (I am, after all, only a simple chemist). Using biomass to replace petrochemicals in short-lived products is good, but using it for pure carbon sequestration might be better. The ordering of those tiers needs further thinking.

But what I am sure of is that using biomass for energy should be our absolute last priority, and only applied in niche cases where renewables don’t outperform it in every single way.

Using biomass right opens up new possibilities

If we stop distorting prices for biomass by paying companies to import and burn it, what kind of new uses could we discover? Removing energy production from the equation opens up new pathways for carbon storage. Here are some of my favourites:

Biochar

Long-term carbon storage in soil, with potential to improve the health of the soil and boost agriculture so we can feed more peopleEngineered wood

Durable wood construction materials to replace energy-intensive and hazardous optionsBiofibre entombment

A very Gothic name for adding biomass to cement, concrete, and composite materials used to build things, ensuring that it stays locked away for at least the lifespan of the buildingMacroalgae abyssal dispatch

Growing seaweed out in the ocean, then sinking it into the deep sea for long-term sequestration. Researchers are now growing seaweed with negative buoyancy, so once you cut it loose it sinks itself!

What can you do?

Write to your MP

It seems like the choice is obvious, and yet, the Labour government has this year approved new subsidies for burning biomass. If you’re in the UK, writing to your MP to tell them you don’t like this is a strong step; calling or meeting with them is even stronger. Biofuelwatch has made this easy for you.

Work within your company or industry

Other options include talking to people within your company about initiatives you have to use biomass, or reaching out to your industry associations to see if they have a position on the topic. Feel free to share this article as a primer, or let me know if you need something shorter.

Vote with your money

As a consumer, buy products made from biomass where you can. The more money the industry gets, the better their products get, and the stronger their lobbying voice is.

Vote with your vote

Neither of the dominant parties seems to be in favour of ending subsidies. Luckily, there are other parties! Pay attention to your local elections and see who is tuned into this issue, then vote for them, volunteer for them, or donate to them.

For students

If you’re a student, consider becoming a biomass researcher, or going into industrial biotechnology. We need as many brains as we can get working on how to efficiently turn biomass into the things we need.