How do you substitute a chemical or material?

"Alternatives assessment" may sound dead boring, but it's dead important

Arguably the most niche field I’ve trained in is alternatives assessment—the practice of identifying the best replacement for a thing (usually a chemical). It might sound simple, but it’s actually its own discipline, with are over twenty different frameworks that attempt to guide people through the process. It’s growing in popularity now as it feeds into the European Safe and Sustainable by Design (SSbD) framework.

The key issue at hand is avoiding regrettable substitution: the replacement of a bad option with an even worse one. If you have a chemical on hand that you know is hazardous, and your supplier offers you one that is not known to be hazardous, that might seem like a good choice. However, “not known to be hazardous” is not the same as “known to be not hazardous”. It might just be that there’s not enough data on the new option to know how hazardous it is.

Practicing alternatives assessment means taking into account how a replacement needs to perform, the scale of supply, how much it costs, and how safe it is, and possibly sustainability metrics. Historically, the focus has been on safer alternatives, but now there’s often an element of sustainability as well. Alternatives assessment is sometimes called functional substitution.

Frameworks for substitution

There are a lot of frameworks for conducting alternatives assessment, all of which offer general guiding principles and/or flowcharts. That’s basically the nature of the practice—each case is individual, so it’s more of an algorithm than a strict set of rules.

Here’s an alternatives assessment framework from the OECD:

That might be a bit much to follow if you’ve not had your coffee, so I’ve done everyone a favour and made a simpler version:

Scope problem and identify alternatives

Basically, you start by identifying how big your problem is (what you’re trying to substitute and why). Then you go on the hunt for alternatives, which includes everything from literature research to attending events to calling up acquaintances and asking if they know anything about vapour degreasing.

Assess risk and check economic/technical feasibility, and sustainability

Once you’ve got a list of alternatives, you proceed to painstakingly gather data on their hazards and likely exposure in the intended use (which together makes risk), as well as their technical performance, cost, availability, and sustainability.

This often gets very research-intensive, especially as considerations like environmental justice become better known—not only do you have to read and weigh up LCAs, but you may have to do some deep supply chain digging to identify how socioeconomically sustainable something is.

Compare and make trade-off decisions

Next is the comparison stage, in which you use your nice neat spreadsheet (you did keep it neat, right?) to look at the different options.

You will almost certainly have data gaps, where there’s not enough reliable information to say whether something is safe, or high-performing, or sustainable. There will also most likely be trade-offs, in which the more expensive option is the safer one, or the safer option is less sustainable. That’s where you pull out expert judgement and make decisions about what you can compromise on, and what you can’t.

Implement your alternative

The last step, but arguably the most important one, is to actually follow through and implement the alternative you’ve chosen. The assessment process is difficult and expensive, and if you don’t follow through on momentum and put it into practice, you’ll have done it all for nothing. So it may be painful (or it may not, depending on your company!) but it must be done—otherwise you wouldn’t have begun the process in the first place.

What’s so complicated about substitution?

All of the above seems a little complicated, but why do we need academic papers about alternatives assessment? Surely one or two frameworks would do if we’re just comparing chemicals, right?

Well, it’s not just chemicals. The real power of alternatives assessment comes with going beyond a like-for-like replacement. When you stop thinking purely in terms of “what other chemical can we use”, you open up a whole field of options, from switching your technology to changing the way the entire system works. Let’s take a look.

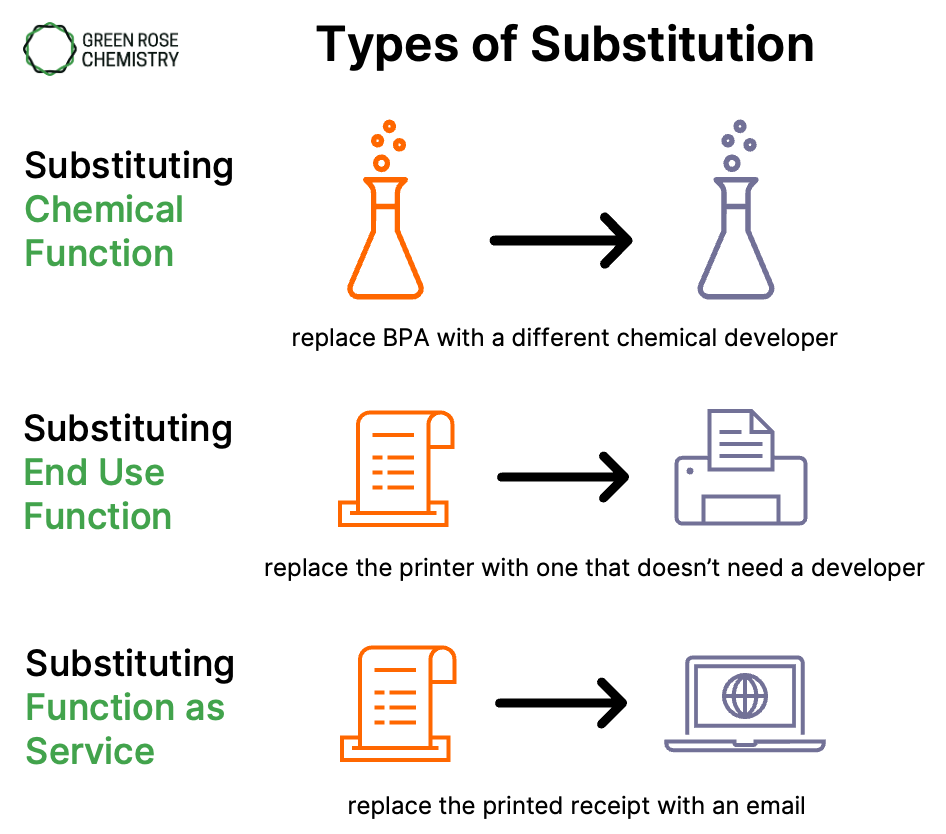

Substituting a chemical function

The most basic type of substitution is essentially a drop-in replacement—you’ve got chemical A that provides a function, and you replace it with chemical B that provides the same function. Your spreadsheet stays pretty simple, with comparable metrics in every category.

In the classic example of bisphenol A (BPA), which was discovered to be an endocrine disruptor (i.e. it messes with your hormones), there was a scramble to remove it from thermal paper receipts. The easiest substitution was to switch to bisphenol S (BPS), with practically no fuss. The astute reader might be able to guess where this is going, based on the name. BPS was practically identical to BPA, which meant it had practically identical endocrine disrupting activity. This is now the classic example of regrettable substitution.

That’s the main problem with drop-in replacements—chemicals that function the same pretty frequently have the same hazards.

Substituting an end use function

To go beyond simple like-for-like substitution, you have to broaden your thinking and ask, “Could I have the same functional product without this chemical?” At this point you start thinking about other technologies, or maybe an intense reformulation effort. Your spreadsheet becomes rather complicated, trying to compare the hazard level of your current 27-ingredient formulation to the new 35-ingredient one.

In the BPA example, you ask what function the BPA is serving (it’s a developer for thermal paper) and how you could avoid needing that function (use paper that’s not thermal paper). So replacing your thermal paper printers with a different technology could remove the need for BPA and BPS, creating a healthier way to print receipts.

Substituting a function as service

Finally, you could broaden your thinking even further, and ask “Could I deliver the function in a different way?”. This becomes a system-wide effort, and often needs to be implemented with the help of a large group of stakeholders. Your spreadsheet becomes a tangled mess of functions and macros.

With thermal paper receipts, you could ask “How could I give our customers information about their purchase without printing?” One potential solution would be to switch to emailed receipts, removing the need for printed receipts altogether.

So should I switch out my chemical, or the whole system?

In the vast majority of cases, companies pick the easy option and do a drop-in replacement. However, when you go broader, to changing the type of product or the system, you do open up your options quite a lot. The process becomes more challenging and complex, and you need to gather more information to make an informed choice, but it can leapfrog you ahead of competitors and position you as a truly innovative company.

How hard is this to do, really?

It’s pretty simple if you’re choosing a new laundry detergent! Actually, I take that back, nowadays you have to consider not just scent and price, but bio vs. non-bio, powder vs. liquid, how concentrated, mail-order or in-store…it’s a struggle. And that’s with all the information being readily available, and not having to defend your choice to angry shareholders or customers three years down the road.

When implementing alternatives assessment in a larger organisation, for a less frequently-substituted chemical or material, it becomes significantly more challenging.

Not only do you have the aforementioned data gaps, but you also have multiple teams, often working in isolation without a shared language. What you need is for your product designer to go to the nearest toxicologist and ask something like “are there other potential proton donors with configurations similar to BPA that are unlikely to bind to estrogen?” But that’s not a skill most people learn in school, or on the job.

There are also skills around scoping the substitution and deciding trade-offs that are not everyday skills for product design or R&D teams. Sometimes you’ll need some expertise from the sustainability or regulatory compliance folks, sometimes you’ll need communication skills in order to give the higher-ups all the info they need to make a decision. Breaking down siloes and building a cross-functional team can improve chances of success.

In short, alternatives assessment is not easy, but it is increasingly important as chemical regulations get tighter and the sustainable transition accelerates. If you never do your own alternatives assessment, you’ll only ever be lagging behind the innovators.