Working as a green chemistry consultant means working with clients who have a wide range of motivations and goals behind their projects. Sometimes I have to answer the question “what is green chemistry?” Sometimes I’m playing catch-up with a company that’s been focused on safety and sustainability for decades.

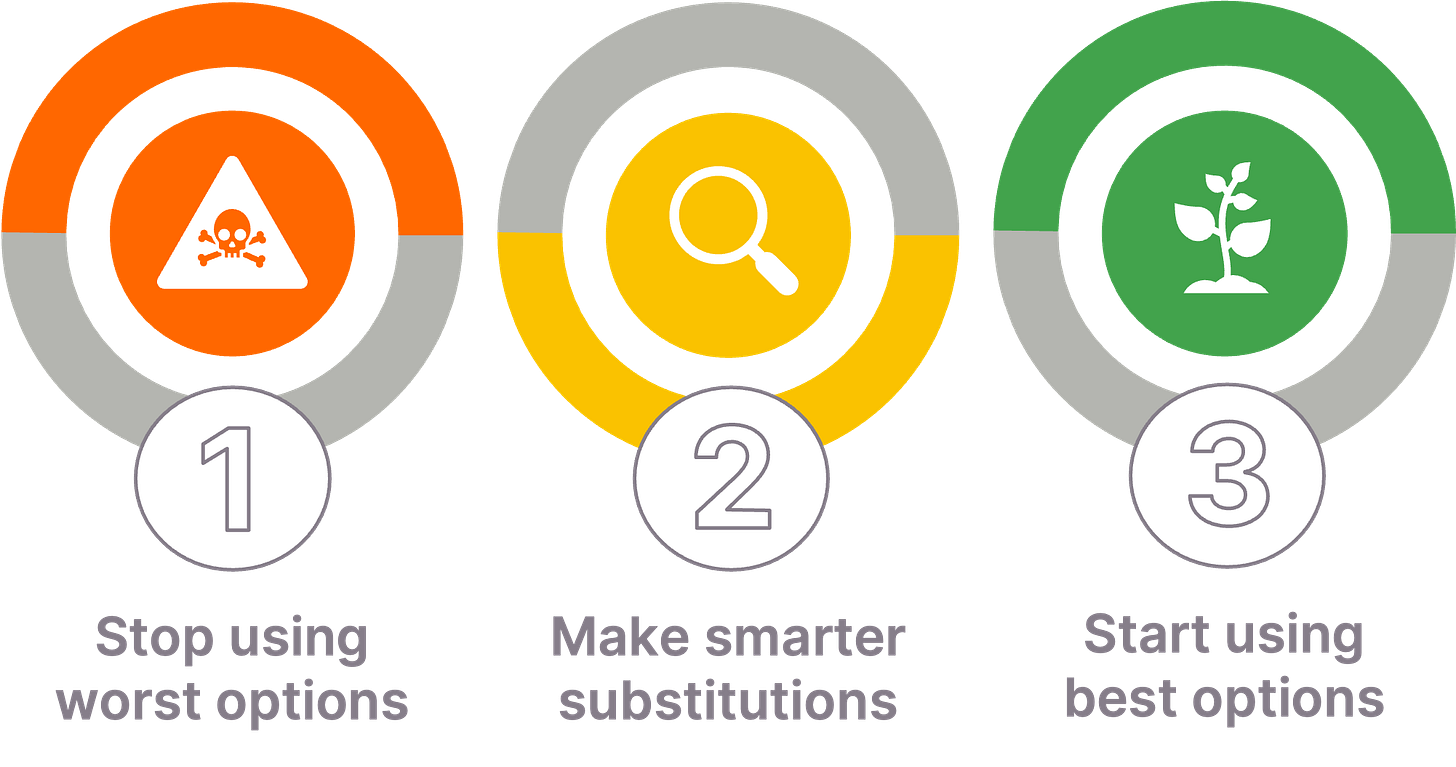

I want to get back on my newsletter game today by dividing this spectrum of green chemistry awareness into three rough stages. This was inspired by a safer chemicals webinar from Lauren Heine, but I’ve broadened it out as it works for sustainable chemistry as well.

Roughly speaking, companies first work on avoiding the worst chemicals, then begin making deliberate, informed substitutions, and eventually start proactively looking for materials that are proven to be safe or sustainable.

Sometimes the stages are a linear journey, but more often they’re cyclical or happening all at once. Sometimes a company is very advanced with one part of a product (like a preservative) but just beginning to consider another part (like a polymer). Let’s take a look.

Stage 1: Stop using the worst options

In stage one of the green chemistry journey, we focus on stopping use of the worst chemicals, or the most harmful processes. This is usually driven by regulatory compliance or risk reduction. In the most obvious case, chemicals are restricted or banned by regulation, forcing companies to stop using them or face legal consequences. Forward-thinking companies will try to predict incoming regulations and move away from chemicals before they’re actually restricted, reducing regulatory risk.

Aside from regulatory risk, using the wrong chemicals can bring business risk. Employees or customers can be harmed by chemicals, leading to risk of lawsuits or reputational harm (we’re leaving aside ethics here and just using a conventional business perspective).

Sometimes, specific chemicals will be targeted by consumer or NGO campaigns, which can cause a company reputational harm and loss of significant market share.

In all of the above cases, the substitution of chemical or process tends to be reactive. A company will go into a defensive mode to avoid losing money, and attempt to quickly eliminate the problem and replace it with whatever comes to hand.

Usually, eliminating the worst options is a good thing, but sometimes it can lead to regrettable substitution, where the replacement is actually worse than the original problem. This is usually due to lack of data about a replacement, or unexpected consequences from using it in a new way.

Companies further along in stage 1 may use restricted substance lists (RSLs), creating or adopting a list of substances that they don’t want in their products or processes under any circumstances. These can come from within the company, if there’s enough expertise in the regulatory, R&D, or toxicology departments, or from industry experts, trade associations, or governments. Using RSLs effectively requires working with suppliers to make sure they understand and have the capacity to provide alternatives where needed.

At some point, companies get tired of playing a game of whack-a-chemical, never knowing when their substitution will go bad, and they start to take a more systematic approach. This brings them to the next stage: more intelligent substitutions.

Stage 2: Make smarter substitutions

While stage 1 is reactive, companies in stage 2 start to think a little more in advance. They see a problem coming and don’t just grab the first replacement they can find—instead, they put some criteria in place for what constitutes a suitable replacement, then systematically look for data to base their decision on. So “a plasticiser that’s not BPA” in stage 1 becomes “a plasticiser proven to have no endocrine disrupting effects or other serious health hazards” in stage 2.

This can involve formal alternatives assessment frameworks, like those developed by the Lowell Center for Sustainable Production, the US National Academy of Sciences, or the OECD. It could also be a custom approach that a company has developed on its own, learning from mistakes and successes with previous substitutions.

There are some essential elements of stage 2 that differentiate it from the quick, whack-a-mole approach of stage 1:

Systematic, criteria-driven approach

Using a structured process with clear criteria for data quality, hazard level, performance measurement, etc. reduces the likelihood of regrettable substitutionDocumentation and transparency

Using a formal process requires each step to be written down, making it easy to justify a decision or revisit it later if new information becomes available.Evidence-based

Reactive decisions can be based on assumptions, hearsay, or industry trends. With a smarter approach, the assessor compares multiple alternatives using the best available data, making the outcome more robust.Stakeholder engagement

Fully assessing the substitution options usually involves talking to relevant stakeholders and experts, ensuring a diversity of perspective. In contrast, a reactive substitution is often decided by one person or a small team, without seeking broader input.Long-term thinking

While in stage 1, companies are thinking short-term and looking to fix the immediate problem as quickly as possible, and often the underlying issue is not solved. An alternatives assessment approach aims to find solutions that are provably safe, sustainable, or both, and is more successful in the long term.

When companies have mastered stage 2 (and hopefully seen the returns on their investment), they sometimes set their sights higher, and start looking for innovative replacements that drive long-term value.

Stage 3: Start using the best options

In stage 3, companies become proactive in seeking out safe, sustainable chemicals as part of their design process. This stage is not about avoiding risks; it’s about innovating to stay ahead of the game. This could mean reformulating with entirely safe ingredients, developing plant-based biodegradable polymers, or investing in a supercritical extraction process to replace a solvent-based one.

Sometimes the best options aren’t on the market yet. Stage 3 often involves partnerships or collaborations, using fresh thinking from universities or start-ups to tackle intractable green chemistry problems. Building good relationships with industry groups and other companies that have the same problems can help, especially when a grant funding opportunity appears—you’ll already have a consortium ready to go.

This stage requires significant buy-in at higher levels of the company, as the investments needed are larger than in the first two stages. However, the rewards can be substantial, especially as consumers become better informed and the transition towards safe, sustainable chemistry accelerates.