We're investing in the wrong climate solutions

Because humans are motivated by novelty (and wealth)

Questions around where to use money most effectively have been on my mind lately. On a personal level, we’re working on retrofitting our home for energy efficiency. From a sustainability perspective, is it better to buy the expensive hemp insulation with lower embodied carbon, which feels good and supports a developing market? Or buy cheap, equally effective insulation and spend the savings on planting trees, which will actually have a bigger impact on greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions? (Seriously, I don’t know the answer to this; somebody please tell me.)

Scaling that thinking to a global level, is the human attraction to novelty damaging our efforts to reach Net Zero? Well, yes. It’s partly that, and partly the problem of measuring business success in dollars made—companies jump on the most profitable bandwagon, regardless of how effective it is in fighting climate change (see also: the petrochemical industry).

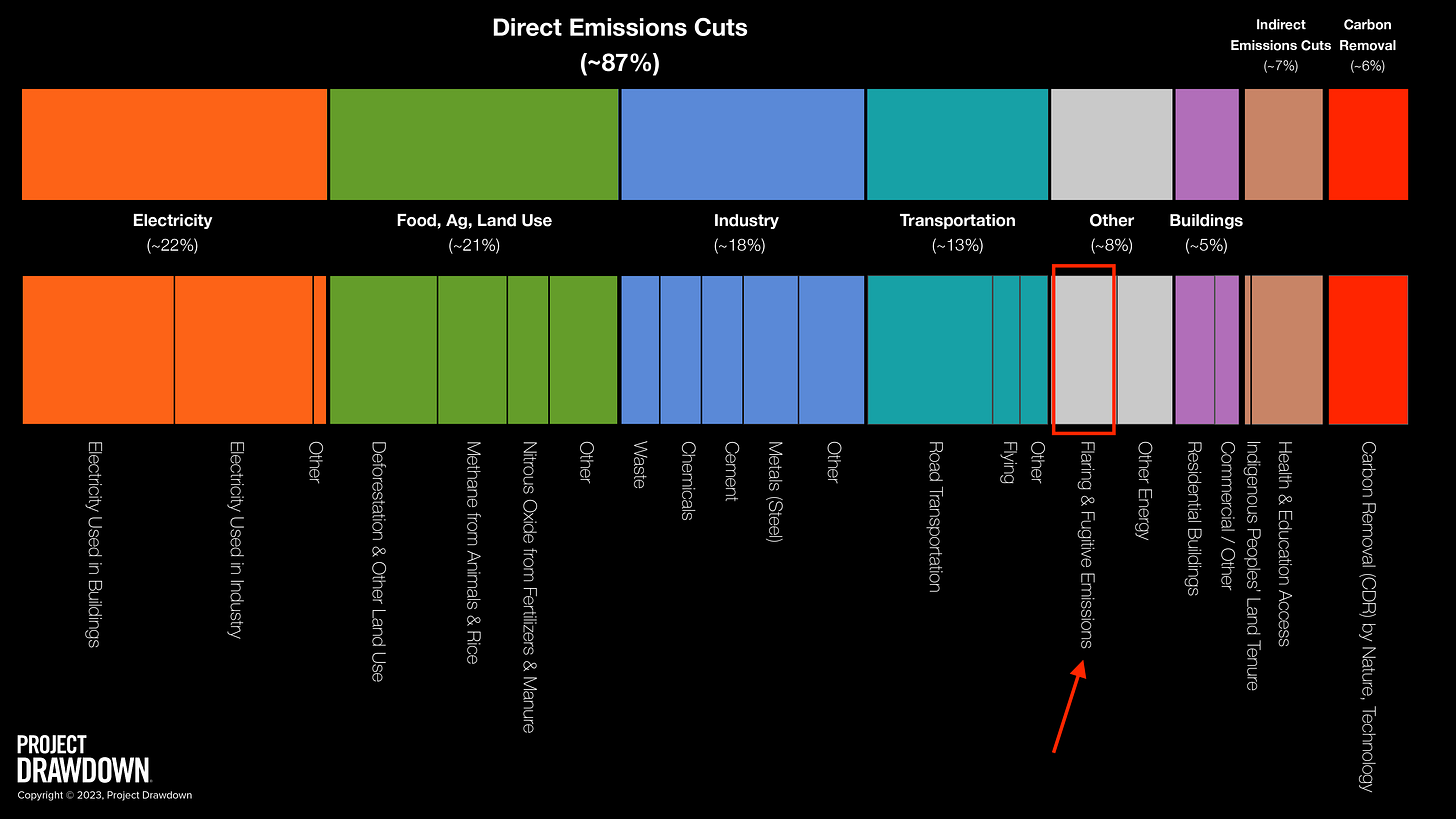

Have a look at the below analysis from Project Drawdown. This is an American non-profit that’s working to direct attention to the right climate solutions—the ones that can be implemented right now, and make a major impact for relatively minor funding. The top bar shows the potential for GHG emissions reductions by sector, in terms of direct cuts. The bottom three bars show allocation of funding to each of these sectors from different sources. For a short overview of this thinking, you can watch Jonathan Foley’s TED talk on climate solutions worth funding.

From the analysis above, about 22% of the direct emissions cuts we need to make come from the electricity sector. Yet the Inflation Reduction Act—the most significant American governmental spending on climate change to date—focuses more than 60% of its estimated funding on clean electricity. Venture capital investment, on the other hand, only slightly overemphasizes electricity, but is way too excited about transport—more than 30% of the funding going to a sector that is only responsible for 13% of the needed cuts. And when we look at philanthropy, the overexcitement is about carbon removal—more than 20% of the funding going to a solution that should only be 6%.

Now, you could argue that this misalignment is actually fine. The US government might be appropriately overfunding electricity because the grid is so outdated and needs immediate fixing, and philanthropists should be funding carbon removal because it’s not profitable but does need development, and maybe there’s a temporary boom in venture capital for transportation that will crash by next year. And it’s true that this analysis is limited both in time and region, so it’s definitely not solid proof.

But for the funding to align appropriately in the long term, there needs to be some sort of overarching plan. It’s not going to happen by coincidence, and we already know the market is not handling the problem on its own. And there’s a major time element to the problem.

94% of the emissions cuts we need to make need to happen before 2030. And that’s actually achievable, if we hit the right levers. Like plugging methane leaks. Which, you may not have noticed, is not being funded by any of the above sources—it falls under “Other”, and makes up a full 4% of the cuts that need to happen.

For me, in the UK chemicals industry, this is a very visible problem. According to CEFIC, chemicals and plastics manufacturing accounts for ~6% of global CO2-equivalent emissions; international aviation, in comparison, is responsible for ~1%. Yet there is quite a lot of specific funding and investment in the UK for sustainable aviation fuel (SAF), and very little for greener chemical manufacturing.

What’s more, the UK government is currently consulting on extending subsidies for burning biomass to the tune of up to £2.5B/year, with the stated hope that companies might eventually be able to capture that carbon with a currently non-existent technology. If we subsidised bio-based chemicals at that rate, not only would we have a lot more sustainable chemicals to play with, but the carbon in the biomass would be locked away, not entering the atmosphere as a GHG.

Exciting new tech is fun to think about, and we definitely do need some longer-term solutions that don’t exist yet. But we don’t have time to fling money after every exciting, unproven technology—we need to fund proven, scalable tech that exists today and can reduce emissions immediately. If you’ve got a few minutes and want to realign your thinking, have a browse through the Drawdown Project’s Solutions Library—and then start agitating for more wind and solar energy.