PVC (polyvinyl chloride, or just vinyl for short) has had a pretty bad year. In February of last year, a US freight train carrying materials for PVC manufacturing derailed in what can only be described as a “fiery wreck”, releasing five tankers’ worth of highly toxic, flammable, and carcinogenic vinyl chloride gas. Close to 2,000 residents from the nearby Ohio town were evacuated, and the emergency management officials handled the incident in the only way possible: quickly venting the rest of the gas into the environment.

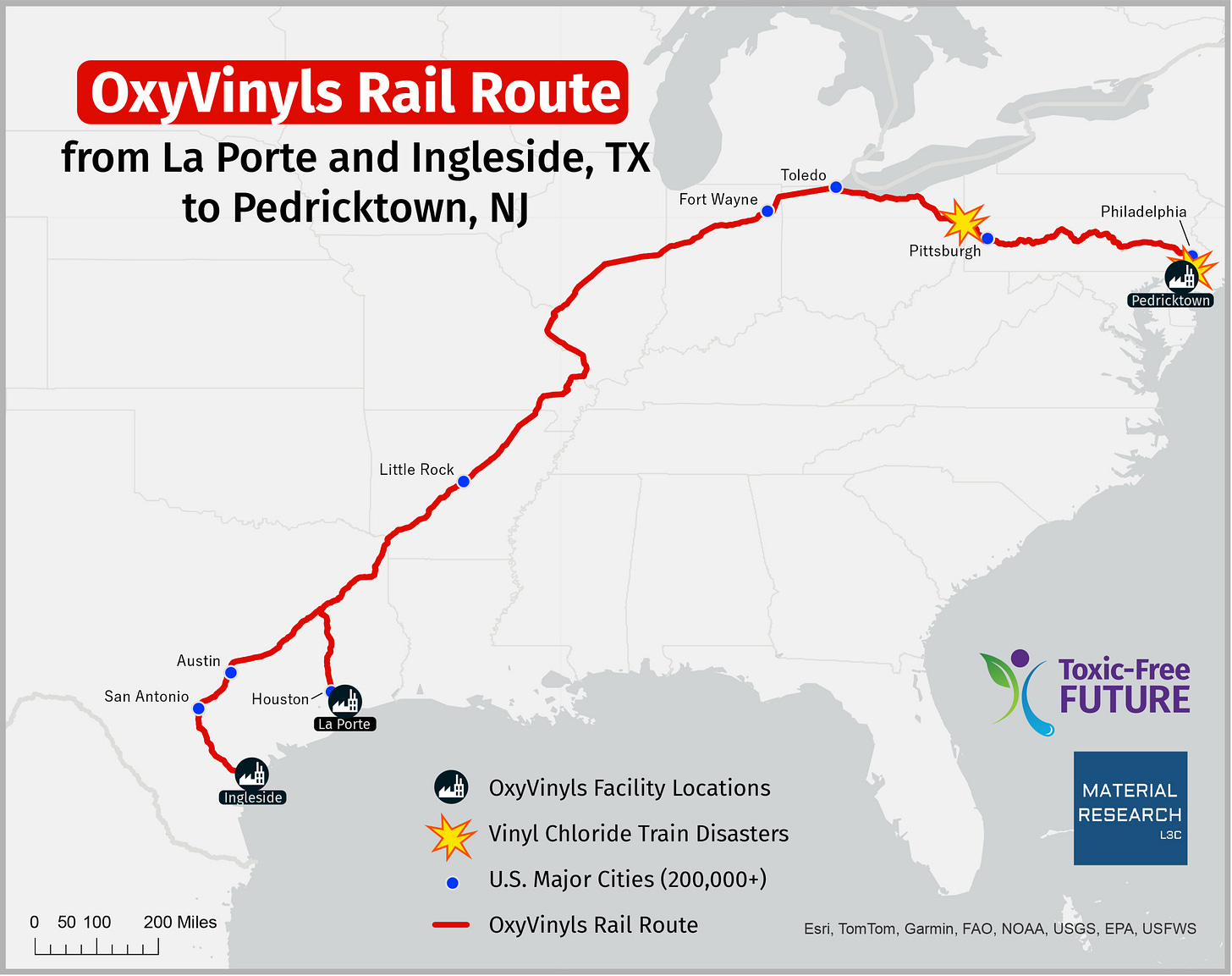

Since then, Toxic-Free Future has put together a report showing the long supply chain that transports vinyl chloride from Texas to factories across the US, the major cities these freight trains pass through, and the communities that are put at risk. They estimate 1.5B pounds (680k tonnes) of vinyl chloride are shipped to these factories every year, and more than 3 million people live within a mile of this train route.

Also last year, US Customs and Border Protection added PVC products to the list of imported goods to be scrutinised for forced labour in the supply chain. Importers must prove that the goods have not been manufactured in China’s Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (XUAR), where a government program of forced labour has made PVC (and other products) very cheap.

Even big market reports are highlighting the problems with PVC. The second bullet point in Mordor Intelligence’s summary of the PVC market notes “the environmental and health hazards during PVC production, usage, and disposal are projected to hinder the market’s growth,” though that doesn’t mean demand isn’t growing. High demand in construction, healthcare, and electric vehicles applications is still supporting sales.

So what can be done to move away from PVC faster?

What is PVC and why do we use it?

Simply put, PVC is a cheap, durable, and adaptable plastic. In our mature petrochemical economy, it’s quite simple to manufacture, using ethylene (which is made in huge volumes in massive steam crackers) and chlorine gas. Reacting these two components gives vinyl chloride, which is polymerised (strung into long chains) to make PVC.

Interestingly, PVC on its own is pretty useless. It’s a brittle solid, and although it was synthesised in 1872, it took over fifty years for chemists to figure out how to load it with enough additives to make it industrially useful. Nowadays, when we use PVC, we add some combination of plasticisers, stabilisers, property modifiers, flame retardants, biocides, and other additives. In fact, nearly all of the plasticisers we use—almost 90%—go into turning PVC flexible.

Once plasticised, PVC can be used in a wide range of applications, from window frames to blood bags to flooring. It makes great electrical insulation, can resist impacts very well, and is very waterproof. As a bonus, it can be made beautifully clear, and doesn’t taint food with any unwanted smells. It’s a plastic that can be made in massive amounts very cheaply, and then adapted to practically any use.

What’s the problem with PVC?

Well, there are a few. First, the whole process of making it is a disaster, from both safety and sustainability perspectives. Every step of the way involves chemicals that are, at best, extremely flammable gases with a high carbon footprint (ethylene). At worst, they make very effective chemical weapons (chlorine gas). Even the “greener” routes to PVC involve all of these, and the less-green routes—still used to produce more than one-third of the world’s PVC—add hydrogen chloride, which is a corrosive and toxic gas, and mercuric chloride, which is fatally toxic by any exposure route as well as mutagenic and very toxic to aquatic life.

And that’s just the reagents. There are also byproducts of this process, such as dioxins, that are persistent organic pollutants, and intense reaction conditions that are dangerous for humans and/or the environment.

After going through all that, we get a polymer that’s so brittle, we need to add at least 10% additives by weight to make it usable, and sometimes as high as 60%. These additives are not chemically bonded to the polymer; they’re just mixed in, which means they can (and do) come out during use. That’s the problem with soft PVC bath toys for kids—they’re essentially phthalate plasticiser bath bombs. We also use PVC in soft tubing for medical applications, increasing the phthalate burden for vulnerable populations like dialysis patients and infants in intensive care.

At end of life, all of those additives make PVC extraordinarily difficult to recycle, as you need different additives for different purposes. To recycle a post-consumer stream of mixed PVC waste, you’d need either an impossibly precise level of waste separation, or very effective additive removal technology, neither of which we have. About 12.5% of European-made PVC is currently recycled, and most of that is window frames being down-cycled. Use of recycled PVC is not popular due to toxicity concerns (all those additives!), so even flooring manufacturers won’t use it if it wasn’t originally flooring.

So most PVC goes to landfill, where the additives leach out, or incineration. When incinerated, PVC generates highly toxic pollutants, like dioxins, which either go straight into the air, or into ash which must then be managed as hazardous waste.

What about PVC and social justice?

Above, I only covered the problems that are inherent to PVC as a material. But it’s irresponsible to discuss PVC manufacturing without discussing human rights issues.

Roughly 10% of the world’s supply of PVC comes from China’s Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (XUAR), largely from two state-owned chemical giants. A thorough report from Sheffield Hallam University and Material Research in 2022 described the links between forced labour, environmental pollution, and the resulting low cost of XUAR PVC. Indigenous Uyghur residents are conscripted by the state to live in dormitories and work in factories against their will, often without pay. The factories use coal and mercury in a particularly damaging manufacturing process, posing an extreme danger to the workers, local environment, and global climate.

Profits are soaring, and a new factory is expected to come online in 2024, adding an additional 49 million tonnes of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere every year.

Surely we can make PVC in a friendlier way?

There is a lot of research going into greener routes for ethylene production, and greener plasticisers and other additives. And not all PVC is made using forced labour! But that’s quite a low bar.

Imagine we were to hold PVC up to the standards that new bio-based plastics are measured against. It’s fundamentally a poor design: a plastic that is made using chemical weapons, needs to be loaded with additives to make it useful, and then ends up being incinerated at end of life because we can’t recycle it. What’s the hook? Why would we invest in this?

The incentive is, of course, it works well within our current chemical industry. You can make massive amounts of it in existing massive facilities, then split it up into smaller batches and add things to it before shipping it all over the world. In a centralised production model it makes a huge profit. If you remove that from the equation (difficult, for obvious reasons), there’s practically no argument for PVC.

So what can we do?

Replace, research, replace some more. There are alternatives to PVC in practically every application—although often with performance differences. Broadly speaking, these include:

non-plastic materials (wood, cloth, etc.)

conventional plastics (some good, some bad)

novel plastics (including bio-based plastics)

The best choice of alternative will depend on the application. The European Commission conducted an assessment of alternatives in 2022 and found a wide range of options, from metal pipes to textile seat covers. Next time you go to buy something made from vinyl, do a quick Google and see what your options are. Or ask your favourite brand if they’ve got PVC-free options—the higher the consumer demand, the more research budget goes into alternatives.

Replacing vinyl flooring with…linoleum?

My personal favourite PVC alternative is a surprising one in the flooring market: linoleum. You might be surprised to learn that linoleum is not actually the same thing as vinyl flooring, as the terms have been used interchangeably for a while. But the original linoleum—now sometimes called natural linoleum—is actually bio-based, biodegradable, and comparatively very safe.

Natural linoleum is made of linseed oil, pine rosin, wood flour, cork dust, calcium carbonate, and pigments, with a woven jute backing. It was popular in the late 1800’s, but began to be replaced by PVC from the 1950’s onwards. It actually performs very similarly to PVC, so is essentially a drop-in replacement, but it’s made of mostly natural, relatively safe feedstocks—no carcinogens or flammable gases needed!

Linoleum can be industrially composted at end of life, and when it’s landfilled, it breaks down harmlessly. Despite that, it is quite durable, and can last 20-40 years with occasional waxing to maintain water resistance (versus 10-20 years for vinyl). It turns out that Victorian era chemistry is actually the bio-based, circular economy hero we all need.

Life cycle analysis (LCA) of linoleum from 2004 suggests comparable or slightly better environmental impact versus PVC, but more recent figures are hard to find. Manufacturing sustainability could be improved by using less intensive oil feedstocks, like tall oil, alternative pigments, or generally intensifying the process to reduce energy and materials waste.

Best of all, there are European linoleum manufacturers who are transparent about their manufacturing sites. With suppliers committed to transparency and good practices, it’s much easier to keep track of where your chemicals come from, and who they harm along the way.